How a teenaged Pau Casals (re)discovered the long-lost Cello Suites of J.S. Bach; or, How to make daily progress for almost 100 years

No Casals, no Cello Suites

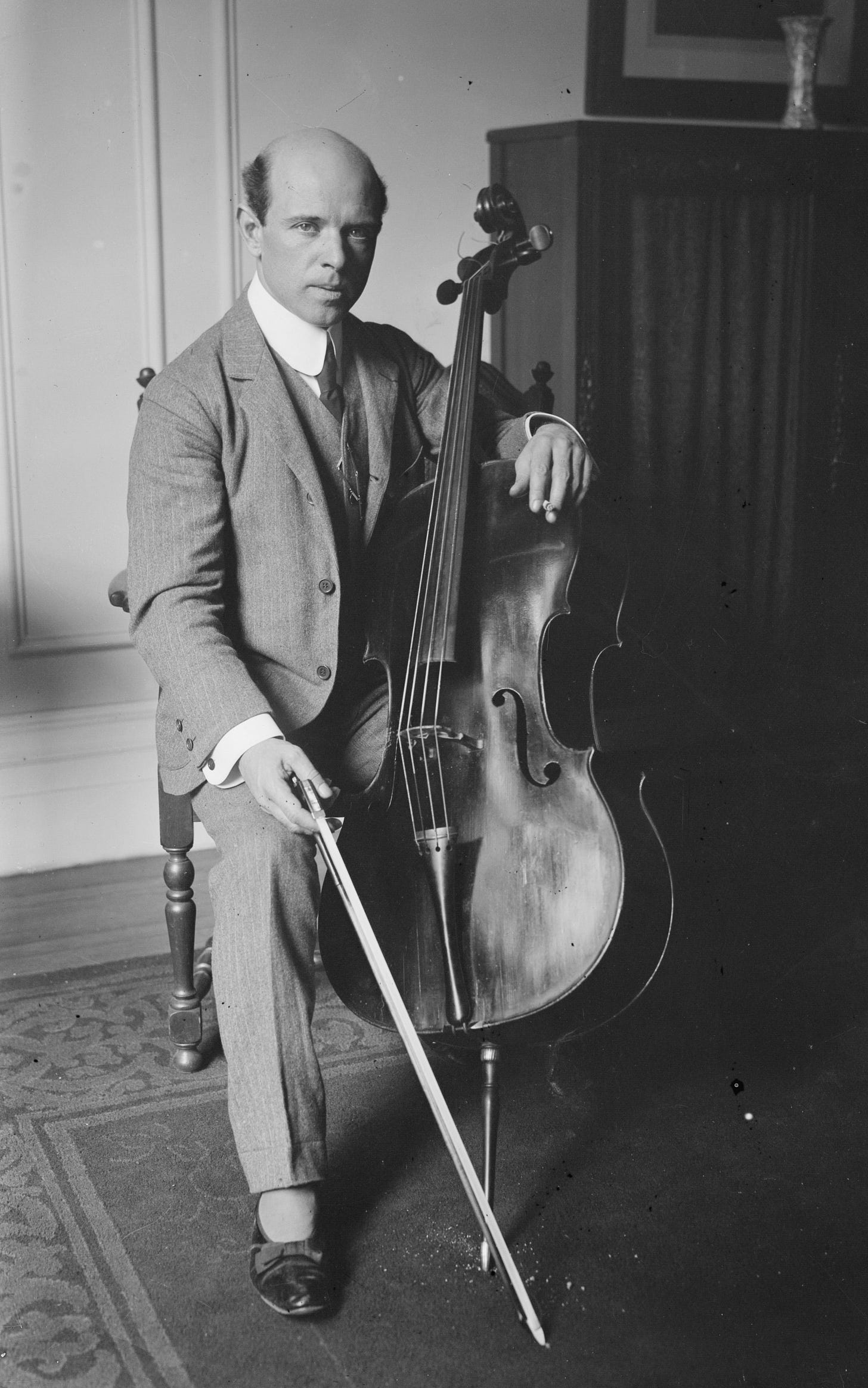

The great Catalan cellist Pau Casals (1876-1973), sometimes known by the Spanish version of his name, Pablo, lived almost began playing music at age 2. He was famous for practicing for several hours every single day, which over 96 years is a lot of practicing. He’s still regarded as one of the greatest, if not THE greatest, cellist who ever lived. He was also a proud and lifelong Catalan resister of the fascist Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, so I’m going to use his preferred Catalan name: Pau.

I was introduced to Casals by my father, Jon A. Jackson, who first played for me a recording of Casal’s Bach Cello Suites. Then he played me an array of other cellists’ versions, and we compared them. I’d heard them before, I realized, but never knew what they were. The Cello Suites are recognizable to lots of people, even those who don’t seek out classical music, because they are ubiquitous. They are ubiquitous because they are beautiful. SO beautiful! But until 13-year-old Pau Casals bought a used copy of the Suites in a music store in Barcelona, they were virtually unknown.

Thought to have been composed by J.S. Bach around 1720 (no original manuscript of the Suites has ever been found), nobody knows for sure what Bach’s intentions were with them. When Casals found them in 1889 he assumed they were practice drills; the six suites, played in order, get progressively more technically challenging. In any case, that’s what Casals used them for, playing them every day for the next 15 years (!?!) before performing them in public in 1904. When he finally recorded them for the first time in 1936, it changed everything.

In Bach’s time, the cello was mainly used as a background instrument. Casals had already become a celebrated cello soloist by 1936, but the revelation of the gorgeous Cello Suites almost instantly made them required repertoire for a new generation of solo cellists. Almost no solo cello music was written before the 20th century; now it ranks second only to piano in contemporary compositions.

As I said, my dad and I spent some time in his basement music room comparing the Cello Suites recordings. We played them LOUD, to really feel that wild cello resonance and I recommend it. Bach manages to make complicated melodies feel simple, the spiraling, repeating themes of the Cello Suites feel inevitable yet mysterious, like the fractal beauty of the whorl of a nautilus shell. You know what I mean. We listened to the following brilliant musicians:

Pau Casals (2:04)

Anner Bylsma (2:06)

Torlief Thedeen (2:21)

Yo-Yo Ma (2:10)

Janos Starker (2:23)

… and yes, each one sounded slightly different. We had our favorites (mine changes all the time; it’s currently Torlief Thedeen and I think my dad would say Janos Starker) and we noticed something else. See those numbers at the end of the names listed above? That’s the total recording length of the respective Suites recordings. They’re all different.

There is no “right” duration for the Cello Suites; there is no “right” way to play the Suites. Because the surviving copies of the original manuscript were not annotated with tempo or technique notations, each interpreter of the music must choose for themself. It’s part of what makes the Suites evergreen: they’re always evolving.

I didn’t even intend to write today’s newsletter about the Bach Cello Suites at all. I was going to write about Casal’s amazing creative work ethic. He practiced up until the last days of his life (he died of a heart attack at age 96) and, when asked why he still practiced so much, he answered: “Because I feel that I am making daily progress.”

As someone currently revising a novel, I wake up every day hoping to also make a little daily progress. As the inspiring case of Pau Casals demonstrates, there is only one path forward: keep practicing. (In my case, keep revising). And my dad, who is now in his 80s, is still writing new stories and novels, too. He feels that he is also making daily progress. So I really have no excuse not to keep going.

“[Daily practice] is not a mechanical routine but something essential to my daily life,” Casals said. “I go to the piano, and I play two preludes and fugues of Bach. I cannot think of doing otherwise. It is a sort of benediction on the house. But that is not its only meaning for me. It is a rediscovery of the world of which I have the joy of being a part. It fills me with awareness of the wonder of life, with a feeling of the incredible marvel of being a human being. The music is never the same for me, never. Each day is something new, fantastic, unbelievable. That is Bach, like nature, a miracle!”

Casal’s serendipitous resurrection of Bach’s Cello Suites is another miracle.

He wasn’t surprised by the diversity amongst the recordings, either. "Well, it must be different, and how can it be otherwise?” he told an interviewer. “Nature is so, and we are nature. The music and everything - everything changes. You see one thing in a way, and minutes after, you are different. So, art is nature. Art is movement. It's color. And, also, our impressions of Bach or any music changes continually...and this is why everything is new."

It’s the first day of the work week. Which means everything is new. Thanks so much for reading, friends. Hope your work is new today, too. A miracle, even.

Or, in Catalan: Gràcies amics meus.

xo Buzzy