Is Stonehenge Art?

Finally, the CARHENGE V. STONEHENGE confrontation you (me) have been waiting for

Dear Treaters, great to be with you.

If you know me, you know I have a thing for Carhenge (a.k.a., “Nebraska’s answer to Stonehenge”). I try to make a pilgrimage there once every year or two (I can drive there from my house, it takes about 2 hours).

I go to Carhenge because I love it, but also because Stonehenge is so far away. I’ve always wanted to visit, but somehow… anyway, I rectified that in September.

Carhenge is a few decades old. Stonehenge is around 5,000 years old. We know very little about the people who built it; we have no idea why they built it, or why it fell out of use around 1600 BCE.

Here’s what we do know. The biggest stones weigh around 25 tons each and they come from a region in Wales, 140 miles away. The stones were precisely placed to align with the winter solstice sunset and the summer solstice sunrise. But what was the intended purpose of Stonehenge? We don’t really know. What is a work of art for? We don’t really know that, either.

I’m happy to say that seeing Stonehenge in person this fall lived up to my own hype. Spotting Stonehenge from the highway is a surreal feeling… it’s so familiar, from a million coffee mugs, cartoons, and Spinal Tap, yet seeing it up close you realize how mysterious Stonehenge remains. The massive size of the sarsen stones lets you know something significant is happening here. But what, exactly?

The whole coffee mug vs. IRL thing got me thinking about that great, melancholy essay by Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1935-1939), in which he argues that the mass production of copies of works of art was changing the meaning of the art itself. He argued that the reproductions caused the original work of art to lose its “aura.”

Well, let me tell you, if Stonehenge has anything, it’s aura. I chose to visit on the autumn equinox, hoping to see some Druidic types, and a few were there (most arrived at dawn; I didn’t). But Benjamin did get me thinking and wondering: Is Stonehenge art?

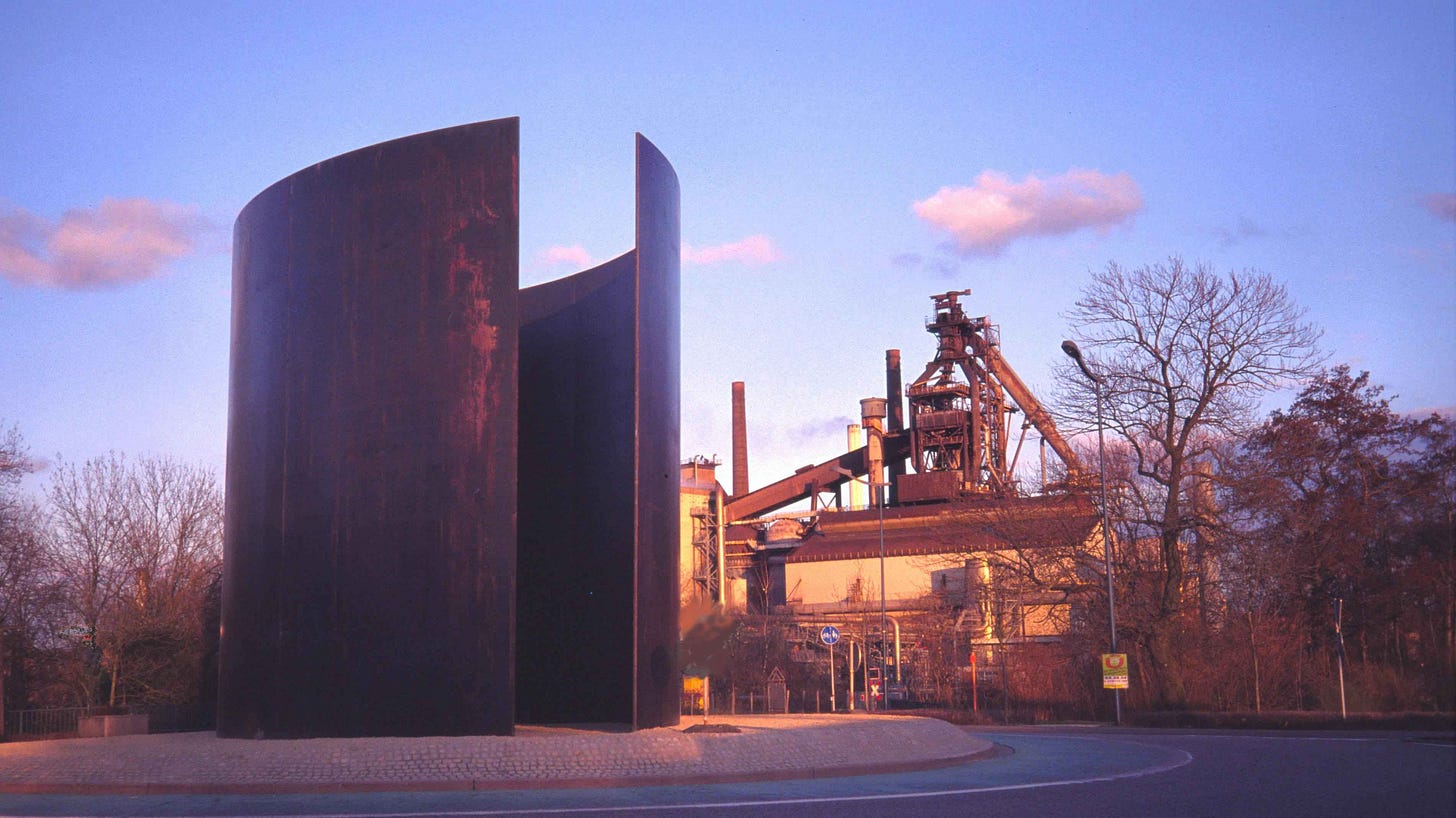

I’m interested in the way we apply the term “art.” A crucifix can be a work of art, or a religious symbol; it depends on the context. Doesn’t it always? The late, great John Berger argued that art is simply a “way of seeing,” which, again takes us back to context. How are we seeing it? What beliefs and questions are we bringing to it?

When I stood in front of the massive, beautiful, even-more-awesome-in-person Stonehenge, I felt its aura. Everyone did. It was a bright, windy, sunny and cold day in September. The stones shone in the sunlight. You can’t walk right up to the stones, though you can get fairly close. But you can’t touch them. So we—tourists from all over the world, plus two busloads of young schoolchildren—lined the perimeter of the stone circle, which is about 100 feet across, and just stared at the rocks. Wondering. Imagining. Bringing our individual expectations to this massive monument.

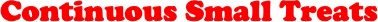

Isn’t that what we do when we stand in front of the Mona Lisa? Or, as I immediately thought when walking up to the Stonehenge circle, the enormous sculptures of Richard Serra?

“Something very important to Serra’s work,” said Emily Rales of the Glenstone Museum, “is that you have to physically be in the presence of one of his works to be able to fully understand it, to comprehend its scale. It does something to you in a visceral way.” That’s the aura Benjamin was talking about. Rales said more: “As you walk interior to its space,” she explained, “it becomes quite obvious that you are the subject.”

That’s what happens at Stonehenge, too. Knowing nothing for sure about its meaning to those who built it, we are thrown back on ourselves to give it significance. An astronomer’s laboratory. A site for ritual sacrifice. A community gathering place. A site for casting spells. A work of art. A tomb. Stonehenge is tuned to the stars. And we are the subject.

“The way we see things is affected by what we know or what we believe,” John Berger wrote in 1972, the same year he won the Booker Prize for his novel, G. He was conflicted. “The whole emphasis on winners and losers is false and out of place in the context of literature,” Berger wrote. As an art critic who believed everything we do is political, he also recognized the inherent potential in the moment, and he deployed it in support of his ideals.

“I have to turn this prize against itself,” he told the Booker Prize committee.

Berger noted that the prize was funded by Booker McConnell and the wealth it acquired through the Caribbean slave trade. “The London-based Black Panther movement has arisen out of the bones of what Bookers and other companies have created in the Caribbean,” said Berger. “I want to share this prize with the Black Panther movement because they resist both as black people and workers the further exploitation of the oppressed.” And that’s what he did.

He turned the prize against itself, simply by seeing the prize differently. Was that money, then, a literary prize or a political tool? Depends on the context.

So, is Stonehenge art? Or archaeology? Mystical ruin? Or just old architecture?

Standing there in front of the stones with all those other folks, we sure stared at it like art. Examining it, both for what it was made of, and what it might mean. Isn’t that the same way we look at art? Giving it meaning, by observing it and imbuing it with our own ideas of significance?

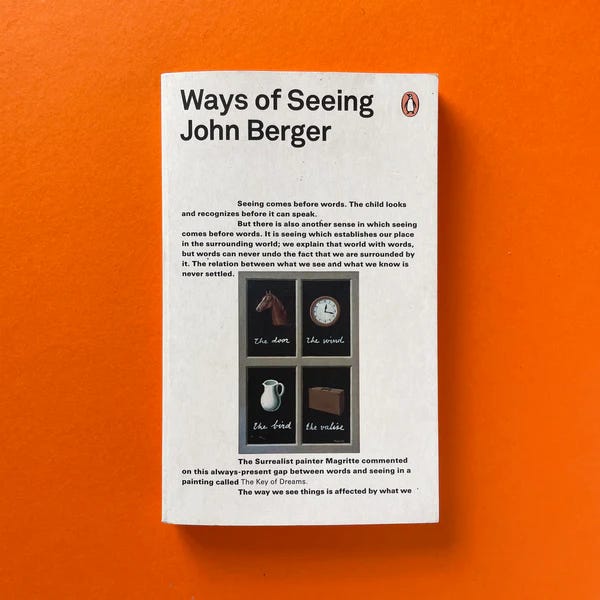

We could approach Stonehenge as a puzzle, a prehistoric problem to be solved. But what can we really hope to discover about these unknown Neolithic people? “No answers,” John Berger wrote of the ancient cave paintings in Lascaux, France (thousands of years older than Stonehenge). “Perhaps there never will be.”

I think the same is true of Stonehenge. “Perhaps we have to be content with intuiting that they came here to experience, and to carry away with them in memory, special moments of living a perfect balance between danger and survival, fear and a sense of protection.” This comes pretty close to a definition of how art works: experience it, carry it away in memory, then reflect on it. Let it change you, perhaps.

“The Cro-Magnons lived with fear and amazement in a culture of Arrival, facing many mysteries,” wrote Berger. And you feel this in your bones, standing at Stonehenge. Whatever Stonehenge was built to encounter, it was something powerful. “Their culture lasted for some 20,000 years,” he wrote. “We live in a dominant culture of ceaseless Departure and Progress that has so far lasted two or three centuries. Today’s culture, instead of facing mysteries, persistently tries to outflank them.”

Maybe that’s what it is about Stonehenge. A million coffee mugs and cartoons disappear when you see it for yourself. It’s got aura. A thousand “Ancient Aliens” episodes haven’t cheapened it. It can’t be outflanked. It sits there, daring you to comprehend. Isn’t that what Richard Serra’s sculptures do?

Once, when visiting Carhenge several years back, I got into a conversation with a guy who works for the (tiny) Carhenge organization.

“Why did they build it?” I asked.

“Guy built it as a tribute to his dad, after he died.”

“Because his dad was really into Stonehenge?”

“Nah, he just thought it was so ridiculous, his dad would have found it hilarious.” He laughed. That’s the Carhenge origin story. You don’t find many like it in history books.

We tend to picture the folks who built Stonehenge as dour Druids but surely they laughed, sometimes, at Stonehenge? They teased someone about a girlfriend. They missed a lost parent. They built an incongruously gigantic monument to those emotions, whether for love or art’s sake. Something beautiful and lasting. It was a way to face the mystery. As are their creations themselves.

Maybe the folks who built Stonehenge didn’t understand it, themselves. Like Carhenge, they just built it because it seemed like the right thing to do. A tribute to everything we can never understand. To me, that’s a definition of art.

“Apparently art did not begin clumsily,” Berger wrote about the cave paintings, a subject he returned to many times. “The eyes and hands of the first painters and engravers were as fine as any that came later. There was a grace from the start. This is the mystery, isn’t it?”

Thanks for reading, CSTers. You’re the best.

xo Buzzy

SOURCES

John Berger, “The Chauvet Cave Painters (ca. 30,000 B.C.),” Portraits: John Berger on Artists (Verso, 2015)

John Berger, “Past Present,” The Guardian, Sat 12 Oct 2002