SPIRIT BLOSSOMS; or, a Q&A with Geistesblüten Magazine (Berlin)

European magazine interviews are just different

Hello, friends, welcome to my international learning curve. I’m delighted to say that the German edition of The Girl with the Red Hair/ Wir waren nur Mädchen (translated by Christine Strüh) will be published in Germany by Aufbau in April 2024. (Note: yes, the same book is titled To Die Beautiful in the USA. It’s a long story.).

This week I got my first interview request from a German publication, Geistesblüten magazine. It’s the culture magazine connected to their art gallery in Berlin, Geistesbluten. I’m so grateful for the opportunity to say a few words about Hannie Schaft here.

I was told Geistesblüten means Spirit Blossoms in German. That’s unusual enough, but then I took a look at the questions I’d been sent. Typically, an American publication will ask an author about their writing influences, or how many words a writer should produce per day. Not these guys! I was a little intimidated by the questions, at first.

So, I turned to my partner, Benjamin Whitmer, an author who’s been interviewed hundreds of times in Europe (his new novel, Dead Stars, comes out in France in April 2024, too!). None of this fazed him. “They ask way more interesting questions there,” he agreed. “Just go for it.” So, I did.

Below are my answers to some questions that actually made me stop and think. Shoutout to Marc Iven and Christian Dunker, the “passionate book lovers” who run Geistesblüten. To make the whole situation even cooler (to an eternal graduate student nerd like me), their book shop is located at Walter Benjamin Platz…?! #arcadesproject4ever!!!

Here’s a great photo of Marc and Christian:

Vielen Danke to Geistesblüten and thanks for the questions. I can’t wait to visit your extremely cool art gallery one day!

xo Buzzy

INTERVIEW with Geistesblüten

What is the biggest risk you have ever taken?

I’m not much of a rebel in my daily life and I try not to pretend to be, even though rebels are the coolest (see: Hannie Schaft). But right at the end of my college years at UCLA, when I was 22, I did something pretty out of character and moved from Los Angeles to Montana to start a romantic relationship with a man I’d known for approximately six weeks. Up until this point in my young life I’d been a good little rule-follower, and I pretty much still am, within reason (although, like everyone, I despise the bureaucracy of pointless rules and try to break those whenever possible).

Back in 1993, as my UCLA graduation date neared, most of my college friends were preparing to do one of three things. A certain percentage wanted to work in the entertainment industry, so they were staying in Los Angeles. The really ambitious kids were making plans to move to New York City, to work in finance or law or some other money making enterprise. And the “slackers” among us (we were Gen Xers, after all; we/Richard Linklater invented the term) were going to move to the obvious place one moved to in 1993 if they were looking for cheap rent and a low-stress job: San Francisco. I know, it sounds insane now, but before the First Dot Com Boom (1995-2000), it was reality. All things considered, I was probably headed for either LA or SF. I was a somewhat employable English Major, with no firm employment prospects anywhere, and it probably would have made sense to stay near the people and contacts I already had in California. But, just like the songwriters say, I fell in love in the spring and, just like they also say, because it rhymes, it made me do some crazy things.

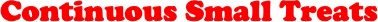

I’m so glad I moved to Montana and took a big chance on something as ephemeral as love. I remember calling my mom from a desolate payphone in Ely, Nevada and informing her of my plans… and she laughed. That was a gift from her, not trying to talk me out of it. The romance eventually came to an end, but this isn’t about that. It’s about the profound feeling of happiness and freedom I felt when, for the first time, I made a Big Decision based on a gut feeling, and trusted myself. It also taught me to trust love. I still do.

You have a Ph.D. in History from UC Berkeley. You are a master of research and tracing, but you yourself are very reticent with personal insights. Is that because you come from a family of writers?

Hey… not SO reticent: see Question # 1!

I did grow up in an extended family/friend circle of writers (my father, Jon A. Jackson, writes mystery novels) and in a series of communities of artists, stretching from Iowa City, to Missoula, Montana, San Francisco, California, New York City, and now Colorado. I think the real advantage of growing up around creative people is the access you get to seeing how artists find ways, despite the financial and personal obstacles that are inevitable, to build a life with space in it for creativity. I’ve been so fortunate to enjoy a creative, fulfilling life and I owe a lot of that to the good models and “bad” influences I had as a child, exposed to an older generation of writers, wild characters, drunks, musicians, filmmakers, hustlers, dancers, poets, cowgirls, painters, cartoonists, cowboys, ghosts, and guardian angels who showed me just how various and dangerous and beautiful a well-lived life can be. They gave me a few things to be cautious of and a lot to aspire to. I’m still working on it.

How would you react if a young person told you that she/he/they can no longer stand this injustice in the world?

I am thankful to the Universe or whoever for the rock-solid sense of injustice that (mostly) only children and young people possess. This human world has always been the site of injustice and maybe it always will be, but it’s always being beaten back by young people who simply cannot stand by and take it anymore. Older people have the same responsibility, but we don’t always come through. I’m grateful to the young people who hate injustice, historical figures such as Hannie Schaft, her friends and comrades Truus and Freddie Oversteegen, Jan Bonekamp, Philine Polak, and Sonia Frenk, and contemporary youth, such as Malala Yousafza, Greta Thunberg, X González, Tiana Day, and the young people throughout the world who are successfully bringing lawsuits against international governments on behalf of the environment. Children understand justice better than most adults. We ought to listen to their wisdom more often.

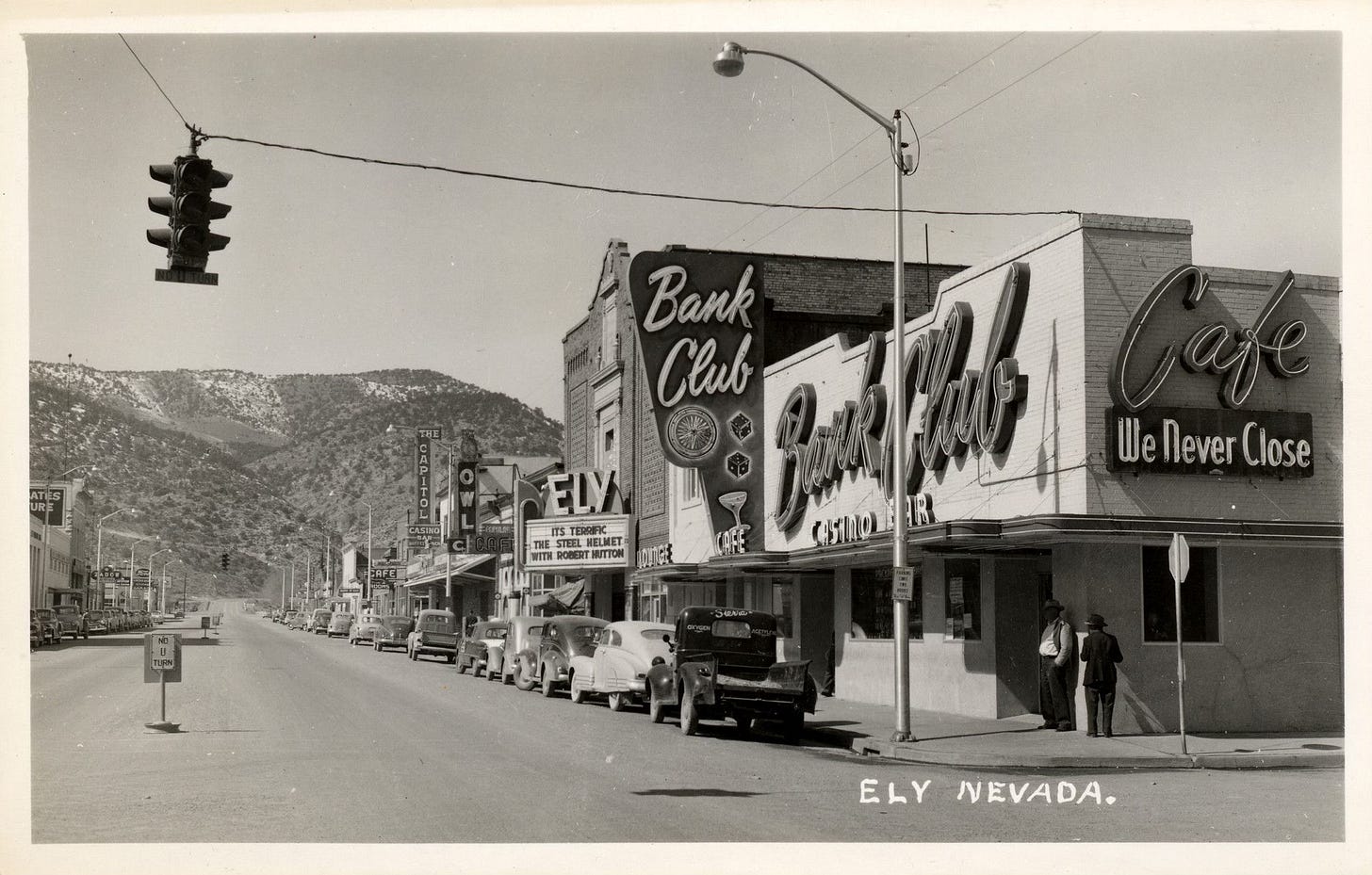

Resistance fighter Hannie Schaft from the Netherlands risked everything. Shortly before her 19th birthday, Adolf Hitler ordered the Wehrmacht to invade Poland. Shortly afterwards, she supported Polish prisoners of war with parcels. When the Jewish star was to be worn visibly from 1942, Hannie helped Jewish fellow students to go into hiding with forged passports. She took part in attacks alongside members of the Communist Party. How did you find out about Jannetje Johanna Schaft?

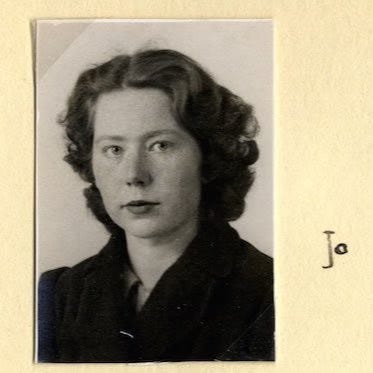

I had never heard of Hannie Schaft until the winter of 2016, when a friend in Amsterdam first told me about her. We then visited the Museum of Resistance (Verzetsmuseum) in Amsterdam and saw a photo of Hannie Schaft and Truus Oversteegen in disguise, along with Hannie’s 9mm pistol and fake spectacles. I was stunned that their names were not more well known outside the Netherlands-–and I decided at that moment to try to bring their heroic story to the wide audience it deserved.

Now that the book is out, readers tell me the same thing: “I can’t believe I never heard of Hannie before!” As a historian, it’s the most amazing feeling, conveying a story of the past into the hearts and minds of readers in the present. I’m very grateful.

In your novel, she is a femme fatale who is initially unaware of her seductive charisma. As soon as she is aware of her effect, she uses it for espionage and as a deadly weapon. Was she really like that?

Hannie began law school right around the time the Netherlands was invaded and occupied by Nazi Germany in 1940. When she started at university she had a reputation for being shy, very smart, and quiet. But as the war went on, that changed. Like most Dutch university students, in 1943 Hannie refused to take a mandated loyalty oath to the Nazi Party and was subsequently kicked out of school. The shock of it radicalized her.

Hannie now fully understood the danger threatening the lives of her Jewish friends, and she realized she had to create a new type of life for herself, too. It was at this point, I believe, she first began to realize her wit, charm, and good looks could be put to work for the Dutch Resistance movement, and she enthusiastically joined in. She was only 22 at the time.

I think what we see in Hannie’s experience is the fluidity of identity in young people, especially those embedded in the chaos of war. As a young woman, Hannie was growing up and evolving anyway, but the fact of the war probably allowed her the opportunity to express herself in ways she had never previously imagined. I believe the high stakes of the places she now found herself in, true life or death situations, unlocked something in her personality and allowed her to blossom in ways that may not have happened otherwise. It wasn’t a game she was playing; the risk was real, so she had to give everything she had to this new persona. She had to fully commit. And, incredibly, she did.

Her beautiful red hair made her stand out to men, but she was also remembered by many because of her striking hair colour. She never really moved away from her neighbourhood, how could she have disguised herself better?

Hannie Schaft was targeted by Adolf Hitler himself as one of the most sought-after Dutch resisters in the Netherlands; Hitler is the person who referred to her as “The Girl with the Red Hair.” Yet her capture and arrest were random and accidental and had nothing to do with her appearance. Nobody ever recognized her red hair until after her capture, once she was a prisoner and her black hair dye began to fade.

Considering the few resources for disguise that were available to her (cheap hair dye, limited extra clothing available, etc), she did an amazing job staying hidden in plain sight. And of course, even once she was captured, she refused to give up her identity, never confirming her captor’s suspicions, even under torture. I don’t think you can ask for more.

An attractive appearance is not everything. But.... (Please complete the thought)

… it sure worked well as a tool for the Dutch Resistance. Again and again, seductive women and men have managed to infiltrate the tightest security during wartime, whether the SS, the CIA, or Ancient Rome. Humans are vulnerable to beauty, despite what we know. “Beauty is an ecstasy;” wrote Somerset W. Maugham, “it is as simple as hunger.” Beauty is a type of power. We cannot reason with it.