"Sometimes a pack needs to bay at the moon together."

"This act of mutual support saves me. People say, How can you go on tour? But for me it’s the other way around. How could I not?" - Nick Cave

“Have you been euphoric in public lately?” - Jennifer Michael Hecht

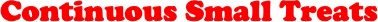

Why, yes, I had the privilege of experiencing public euphoria just last week, while watching the always-incredible Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds perform on the final night of their 2025 North American WILD GOD tour, at San Francisco’s Bill Graham Civic Auditorium.

I’ve seen Nick Cave perform many times since the early 1990s and it’s always a memorable night, but every show delivers a different emotional experience: from wild lust to raw power, and always a glorious expression of rage (in those days, Cave’s band was known as “the most violent band in Britain,” known for getting in fights with their own audience). The performances were always exciting. But this tour felt different: a singular, communal, deeply examined celebration of love. And a public, shared experience of euphoria. It was the first one of those I’ve experienced in this country in a long time. God, it felt good. And I found myself thinking about The Happiness Myth, a wonderful book about how humans find meaning in our lives, by one of my favorite writers and thinkers, Jennifer Michael Hecht.

“Happiness requires some public processing of grief and fear,” Hecht writes in The Happiness Myth: Why What We Think Is Right Is Wrong (2007). As a historian of Ancient Greek culture, Hecht compares contemporary concerts like Nick Cave’s to the riotous festivals of the Greece of a few thousand years ago.

“In ancient Greece, people believed that participation in [communal public] rituals… kept the community going, magically,” she writes. “For us, if we join our communities’ rituals, then our community rituals continue to exist, with people like us in them. Community spirit and team spirit are both called spirit for a reason. Community and team are where we got the idea of spirit, and they are what still delivers.” As Hecht notes and as I witnessed last night, being part of a crowd at a big, loud, beautiful concert can deliver it, too.1

One thing to know about Nick Cave in 2025: he’s not the same snarling goth he was when he first got famous with his Australian punk band The Birthday Party (1977-1983), or when he moved to Berlin and started showing up in cool AF Wim Wenders movies (Wings of Desire, 1987), or even when he started fixating on the old, weird America and released an entire album of Murder Ballads (1996). The first time I saw him perform ca. 1990, he was addicted to heroin and arrived onstage at a grimy Los Angeles club four hours late. Now, sober for over 25 years, he’s still got demons to exorcise, but in 2025 he’s also the survivor of yet further personal devastation: in recent years, two of his children died. It changed him. To watch Cave perform in 2025 is to witness an artist clinging explicitly to the only salvation that matters to him anymore: Love, and our bonds with each other.

“The young Nick Cave could afford to hold the world in some form of disdain because he had no idea of what was coming down the line,” Cave told journalist Sean O’Hagan for the book-length interview they released in 2022, Faith, Hope, and Carnage . “I can see now that this disdain or contempt for the world was a kind of luxury or indulgence, even a vanity. He had no notion of the preciousness of life—the fragility. He had no idea how difficult, but essential, it is to love the world and treat the world with mercy. And like I said, he had no idea what was coming down the road.”2

Now, when Cave and his longtime bandmates the Bad Seeds take the stage, it’s an explicitly spiritual experience they’re delivering. He still sings explosive songs from his youth (“From Her to Eternity,” “The Mercy Seat”) but delivers them with a deeper, more personal understanding of the meaning of life and death. Now, when he performs his song, “O Children” (2004), it’s prefaced with a direct address to his adoring audience: “This is a song about where we all are now, at this moment in history: a civilization unable to care for its own children.” He doesn’t just mean his own kids; he means all our children, and all the children to come in the future:

O children

We have the answer to all your fears

It's short, it's simple, it's crystal-clear

It's roundabout and it's somewhere here

Lost amongst our winnings

“Always bracing against pain is too exhausting, we need to embrace it now and again,” Jennifer Michael Hecht writes, explaining why our ancient ancestors structured their civilizations around public festivals and performances. “We need to embrace [pain] now and again… It would let the mysterious power of the crowd develop intensely, to the point of euphoria, and it would let us have a public private life.”

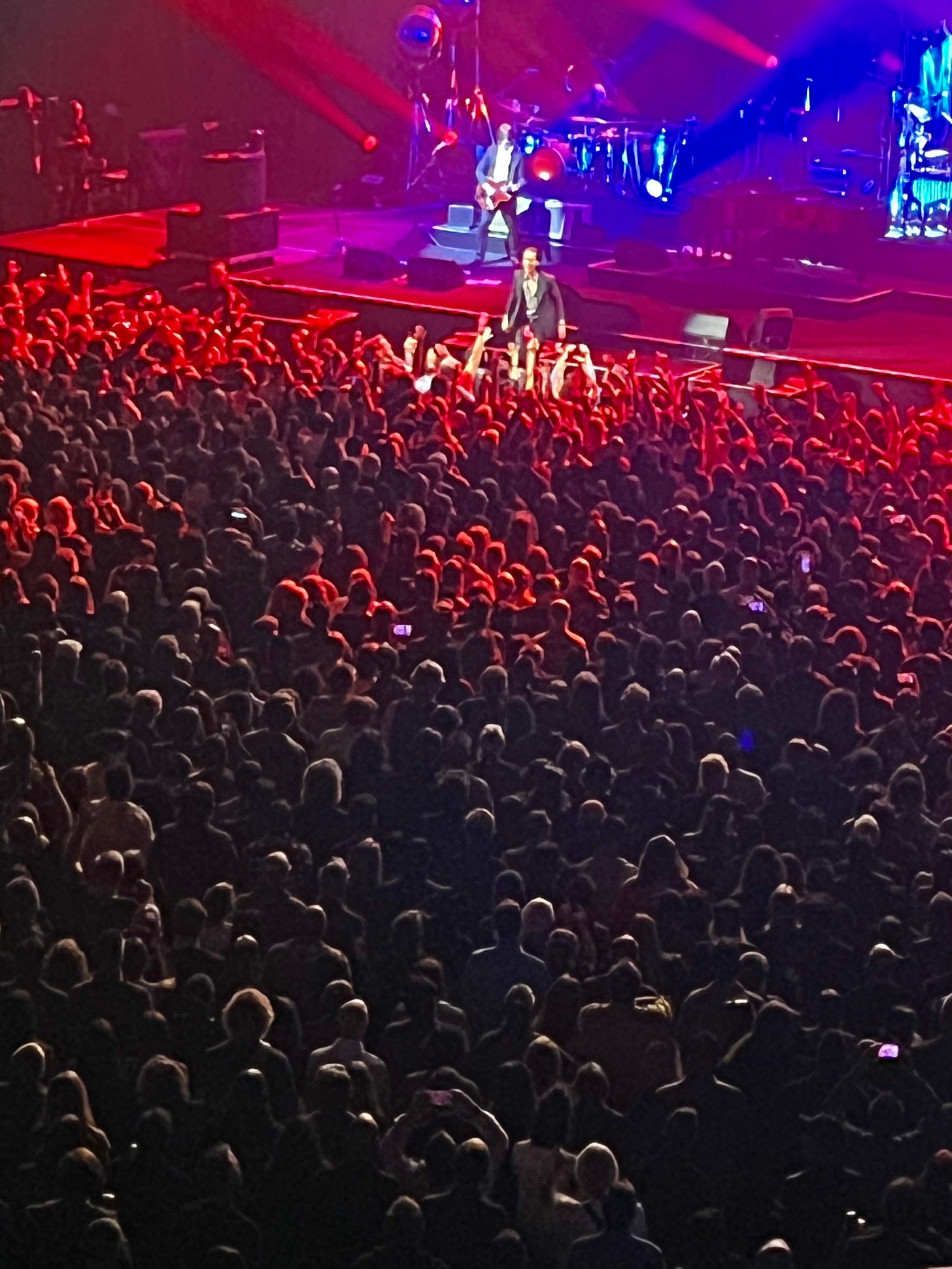

Enter Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds. In the late 20th century people went to a Nick Cave concert to sing, scream, and maybe join a mosh pit. Now, in the early 21st, people still do all those things, but also to weep, in public. I know I do. When Nick Cave stalks the stage, shouting at us, “You’re beautiful! You’re beautiful! You’re beautiful!” we need to hear it; we have to believe it. Even if we don’t believe it. We know we’re not winning, as a civilization or a species. We’re failing. The only thing that can save us is love… and each other. As Cave sings in one of his recent songs, “I Need You” (2016):

We love the ones we can Cause nothing really matters

And somehow, singing it with him and all the other people in the Bill Graham Auditorium, it makes us feel better about our bleak condition, because we’re singing it together. As we live through a historical moment in which our (unelected) leaders try to convince us that empathy is a “weakness,” Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds offer an alternative. Maybe nothing really matters. But we love the ones we can. We love the person we came to the show with and the other 8,498 people who were drawn here like magnets to witness Cave’s vulnerability and grace in the face of all that nothingness. We have nothing. Nothing but each other.

“Gatherings are a necessary condition for the survival of the group, both really and magically,” Hecht writes in The Happiness Myth, yet, “more than any other people in history, we are enabled by our culture to feel independent. Which means we’ve leaned away, as a culture, from one of the foundational elements of what truly makes people happy: ecstatic group gatherings.” Gatherings such as festivals, parades, live sports. Like a gloriously emotional Nick Cave concert.

“When Arthur died,” Cave said, referring to his son’s death in 2015, “I was thrust into the darkest place imaginable, where it was almost impossible to be able to see outside of despair… The concerts that I did following that, too — the care from the audience saved me. I was helped hugely by my audience, and when I play now, I feel like that’s giving something back. What I’m doing artistically is entirely repaying a debt… It’s difficult to talk about, but the concerts themselves and this act of mutual support saves me. People say, How can you go on tour? But for me it’s the other way around. How could I not?”3

A 2025 Nick Cave concert is a reminder of how much we need each other. We can do a lot of things in isolation, but not the important things. Again, as Jennifer Michael Hecht writes, “we really aren’t independent; we are a pack—a pack with off-the-charts sophisticated minds and hearts that we use almost entirely to monitor the pack and respond to its every shiver of experience. Sometimes a pack needs to bay at the moon together.” Or, as Nick Cave put it the other night:

I saw a movement around my narrow bed

A ghost in giant sneakers, laughing stars around his head

Who sat down on the narrow bed, this flaming boy

Said, we’ve all had too much sorrow, now is the time for joyLove,

Buzzy xo

Jennifer Michael Hecht, The Happiness Myth: The Historical Antidote to What Isn't Working Today (San Francisco: HarperOne, 2007).

Nick Cave and Seán O’Hagan, Faith, Hope and Carnage (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022).

David Marchese, "Nick Cave on Faith, Hope, and the Meaning of Life," The New York Times Magazine, September 12, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/09/12/magazine/nick-cave-interview.html.